AC4CA : THE AUSTRALIAN CENTRE FOR CONCRETE ART

JULIAN GODDARD FREMANTLE 2014

The Term 'Concrete Art' has been contentious since its formulation by Theo van Doesberg in Paris in 1929. Whilst it represents what may well be the most radical turn in art in the 20th centurt it is still under-theorised and consistently misrepresented.

Emerging out of Russian Constructivism it registers a political shift in the dialogue of art away from nineteenth century aestheticism and the intellectualism of earlier twentieth century avant-garde practices such as Cubism or the spiritualist purity of Suprematism. The aberrant child of De Stijl – Concrete Art dismissed its parent’s addiction to spiritual meaning as left-over-occultism masquerading as abstraction. Van Doesberg’s infamous stoush with Piet Mondrian resulted in his jettisoning any idea of the primacy of the need for meaning in art through the formulation of a new practice that has no overt or covert desire to say anything at all. This paucity or silence of intention and meaning is a complete rejection of the Enlightenment cannon of art driven by the unresolvable binary tension of reason and expression. On the contrary, Concrete Art embraced a thoroughly modern and democratic possibility for art practices. Pragmatic (especially American Minimalism) and fundamentally dispassionate, Concrete Art is ironically still able to mount an opposition to the excesses of contemporary art and its overblown narratives.

Usually misunderstood as a conjunction of abstraction (which van Doesburg vehemently rejected) and design, Concrete Art is more a form of realism that rejects any need for explanation, translation or interpretation. It is non-reflective; only being itself. It has no story or ‘message’ to tell, instead relying on only its presence to produce experience. As such it is very ‘un-contemporary’ - sitting outside of the legitimations of ‘the back story’ or the power of the branded (affiliated narrative) object. Instead Concrete Art has nothing to say at all. It is what it is and that’s all. Like an act of deliberate dumbness – it admonishes the seduction of meaning.

One of the stranger conditions of contemporary Western society is its inability to ‘do beauty’ without the necessity and drive to understand it. Again post-Enlightenment science has tried to distance us from the experience of beauty through its insatiable hunger for knowledge, but despite countless attempts at understanding and explaining the experience of beauty (aesthetics), it has somehow managed to elude any final definition. Instead it occupies an anomalous site of unknowing. The word ‘beauty’ really should be a verb, not a noun, because it is part of an active experiencing of the world – libidinal life reverberating with dis/pleasure. Concrete Art seems to occupy a similar libidinal space.

Project 7 Alex Spremberg

Queensgate car park 2003

In late 2001 I initiated a conversation with a group of artists and colleagues that Glenda de Fiddes and I had worked with over the previous decade through Goddard de Fiddes Gallery.1 The discussion began around the need to delineate their work from others who were beginning to ‘cash in’ on the renewal of minimalist abstraction that had distinguished the gallery’s exhibition programme. Initially the plan was to make an emphatic statement that could not be replicated. However, this quickly gave way to a defence of the critiques that such art was elitist, a ‘modernist revival’ or fundamentally private and failed to embrace the original aspirations of Concrete Art with all its hopes for a democratic and universal art that would enliven the lives of others.

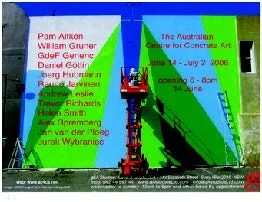

The first AC4CA participants were artists Alex Spremberg, Andrew Leslie, Trevor Richards, writer and curator Chris Hill and myself. We were quickly joined by artists Paul Hinchliffe and Jurek Wybraniec. The initial meetings, held in a coffee shop in Fremantle, eventuated in evening strolls around the streets of Fremantle looking for possible walls that we might paint. The name, ‘Australian Centre for Concrete Art (AC4CA)’ was debated and adopted. The use of Australian was consciously chosen to signify that an organisation in Perth/Fremantle represented a tendency in art that professed to have an ‘Australian’ purview. This was meant as a retort to the endless claim of national representation in art claimed by institutions in Melbourne and Sydney that constantly made no reference to the production of art in Western Australia. A reactive and parochial act for sure, but one that was deliberately engineered to draw attention to the dichotomy of the inside/outside pressure on artists in Perth/Fremantle.2 The AC4CA was registered as an incorporated body in May 2002 with its stated objectives being:

‘… to establish a national/international foundation which promotes artistic activities related to the guiding principles of the international movement known as Concrete Art. The general principles of Concrete Art reflect an emphasis on the material basis of art making, non-representation, purity/singularity and a focus on the process of construction’.3

Over the past 10 years the AC4CA has grown into an international network of artists holding regular collaborative exhibitions in and outside Australia and continuing to foster public wall-works. To date there have been 23 projects (21 public wall works and two large museum exhibitions), 4 smaller gallery exhibitions, two sets of prints (with catalogues) and several unrealised projects. The endeavor has been a slow one and has gradually evolved and responded to the wishes of its members. Over the past 12 years there have been 21 members of the group with membership by invitation.

AC4CA Project 1 – Jurek Wybraniec begins the first project, Summer 2002

The first wall-work, AC4CA Project 1, was realised during the summer of 2002 on a large dark blue wall surrounding a run-down, funeral parlour parking area next to ‘the coffee strip’ on South Terrace, Fremantle. The large painting by Jurek Wybraniec was an extension of his studio practice featuring his signature acidic pink of the time (with a similar yellow and blue). The wall-work extended his interest in the tension between a Pop/camp/kitsch aesthetic and the strictures of Minimalism into another scale. By 2002 Jurek had developed an installation strategy in his work that often involved the use of the gallery space in determining the size and shape of the work being installed. This included wall-works made in response to the geometry, layout and proportions of the gallery. The work for this wall used a similar starting point, taking into account the slight decline of the level of the ground from right to left as a way of determining the logic of the image. The rectangles were based on the anamorphic CinemaScope screen aspect ration of 2.35:1.

At the time, Jurek’s studio practice was focused on a series of ‘doppelgänger’ paintings by which two seemingly identical images sat next to each other, begging comparison. This wall-work’s highly ‘public’ position in a space directly opposite the social hub of Fremantle, attracted curious attention – especially while it was being painted. The main reaction to the wall painting was perplexity, with people asking what we were doing and “is that all there is to it?” and of course – “what does it mean?”. This work was quickly followed on the same wall, painted over Jurek’s, by a beautiful piece by Trevor Richards that featured his signature discs of the time. Trevor’s wall (2002), as with Jurek’s, was an extension of his studio/gallery practice - in particular his BYOG project that begun in 1999 by which he restricted his practice to four colours: blue, yellow, orange and green. The work had a remarkable reflection in the shop windows and glass doors across the street.5 Unfortunately the wall was destroyed a few months later to make way for a property development.

Also in 2002, AC4CA Project 3 was made by Dutch artist Jan van der Ploeg. Visiting Perth for an exhibition at Goddard de Fiddes Gallery, he took advantage of the offer of a wall in Cantonment Street, Fremantle. Jan’s image was a transcription of his ‘grip’ paintings; a series of works based on the lozenge-shaped indentation used for lifting found on the side of cardboard boxes (the grip shape is a rectangle with rounded ends). The huge black, blue and yellow interlocking shapes had a dramatic presence that stayed in place for seven years before being covered by Jurek Wybraniec’s third wall work.

Wall painting Project 4 (2002) was a significant shift for the AC4CA. For his second contribution, Jurek Wybraniec used an abandoned water tank on the coast a few kilometres south of Fremantle in Coogee. Visible from the main road between Fremantle and the industrial areas to its south, Jurek chose this time to paint the concrete tank in a base-colour of pink covered with a regular pattern of large blue dots. The painting was consistently graffitied and Jurek would re-paint one colour at a time leaving the graffiti-covered surface as a negative space. This ‘dialogue’ with the graffiti painters went on for months attracting public comment in the local press. Commuters took the time to write to the local paper asking what was going on either condemning the tank as an eyesore or encouraging the ongoing ‘paint war’ between Jurek and the graffiti writers. This back-and-forth ‘paint war’ went on for several months before the tank was destroyed to make way for a marina development – the subject of the protests of the graffiti writers.

Helen Smith’s work in the early 2000s was based around shifting visual fields of colour often using an ovoid shape that formed a tension against its ground. Her first AC4CA work (Project 5, 2003) on a huge wall in North Fremantle allowed for a new possibility in the way in which her work could be perceived. Located perpendicular to the Perth/Fremantle railway line, this work was virtually only viewable from a passing train. The 6.5 x 27 metre work consisted of a dark green field with lighter green ovals arranged in a grid. As the viewer moved past the image the ovals seemed to compress into circular dots before disappearing as the train sped past the wall.

John Nixon’s 2003 huge wall work (Project 6) close by to Jan van der Ploeg’s work was an emphatic minimal statement. A giant orange circle on a white background, the work could hardly not be noticed and drew plenty of comment, especially for its apparent similarity to the national flag of Japan –‘circle of the sun’. This wall grabbed the locals’ attention in a way none of the previous walls had done. Its sheer size and the exaggerated reduction of the image gave it a presence that people either loved or found annoying. But most importantly it was noticed.

By the end of 2003 the group had made six large ‘public interventions’ through their wall paintings, with three of them - projects 3, 6 and 7 - close to each other in the streets of Fremantle. Despite the strength of their visual presence the walls had proved popular with many of Fremantle’s residents, shopkeepers and visitors. But it was the next project, number 7, that really prompted a dialogue with the local community. The City of Fremantle, through the support of Councillor Helen Hewitt, commissioned the AC4CA to make a design for the re-painting of a multistorey, Brutalist-style municipal car park built in the 1970s and in dire need of a revamp. Alex Spremberg’s ‘user-friendly’ design and colour scheme for the building began with painting the low ceilings inside the building a light blue ‘to give an impression of open space and associations to the sky’.

“Instead of hiding the building I chose intensive colours that gave it presence and made it visible from far away. Emphasising the horizontally recurring units with a dark blue and interrupting them by highlighting the vertical structure with a bright orange colour accentuated the two fold dynamic of the building”.6

Spremberg’s exceptionally bright colours used for this makeover shocked the staid conservationist and heritage clique in Fremantle and bought the AC4CA activities into conflict with those who saw the car park re-paint as ‘garish’. A public meeting in the Fremantle Town Hall to discuss the validity and value of the AC4CA’s interventions turned out to be a flop with only one Fremantle resident really objecting to the car park’s colourful presence. The car park project threw a spotlight onto the AC4CA and its activities in Fremantle which had until then been fairly benign and easily tolerated.

However, this very large project brought strong debate - played out through the local press questioning the validity of the AC4CA and its unsanctioned activities that had evaded the standard planning approvals usually required to alter a building. And whilst the car park project brought protests and sparked a debate it also upped the profile of the AC4CA and the previous projects which suddenly became to be seen as a threat to the heritage values of the community. The debate widened to become a larger conversation about the validity of public art, not only in Fremantle but also Perth that raged for the following three years. A City of Fremantle councillor who was also the Deputy Mayor and President of the Fremantle Society7 saw the colourful scheme for the building as “a nightmare proposal” suggesting instead the building should be painted over with a military-like green camouflage paint.8 He continued to rail against the “ugly edifice” into the following years, stating in 2005 that “It has been an eyesore, now it is an artsore[sic]”9, and later declared the car park had been labelled “one of the ugliest buildings in Perth”10 (he neglected to say by whom). This councillor still continues to denigrate the building’s colourful presence, along with most other forms of built environment that could be considered modernist, as an affront to the heritage values of Fremantle. Ironically, while the building’s aesthetic drew strong criticism its revenue from car parking grew quickly because of its new identity and more friendly and safer atmosphere. Despite the initial backlash and some ongoing grumpiness, the ‘car park’ quickly became an icon of Fremantle and has been celebrated across Australia for its innovation and is considered the largest public artwork in the Southern Hemisphere.

Alex Spremberg and Trevor Richards at the launch event for Project 7, Queensgate car park

Following the car park project the group formulated a clear statement of intent about its activities in Fremantle: “The AC4CA wall projects are an ongoing contribution to the community in an attempt to bring joy and pleasure into the everyday fabric of Fremantle”. Emphasising the group’s desire to make a positive contribution to the daily life of Fremantle citizens, the statement not only embodies the founding aspirations (of joy and pleasure) of Concrete Art but also continues to be a guiding principle for the group’s objectives and projects in contemporary everyday society.

Swiss artist Daniel Göttin first spent time in Fremantle in 1990 as artist-in-residence at the Fremantle Artists Foundation and had since continued to exhibit regularly in Perth at Goddard de Fiddes Gallery. His practice is situated in the history of Concrete Art in Switzerland which had enjoyed significance since the 1930s (see Hubert Besacier’s essay). His wall in Pakenham Street (AC4CA Project 8, 2004) continued his interest in the articulation between colour and pattern. The elongated wall supported a work generated by its context that refers not only to the proportion and design of the wall itself but also to the physical environment with the aqua blue horizontal bands echoing the sky and nearby ocean. The colour lifted the experience of the space around it, making its presence extend well beyond itself.11

Between Jurek Wybraniec’s first work in the early summer of 2002 and Daniel Göttin’s Project 8 in late 2004, the AC4CA had grown to include artists Jan van der Ploeg from the Netherlands and John Nixon from Melbourne,12 as well as Perth-based artists Rauno Jarvinen and Joerg Hubmann. After a flurry of walls had been completed in the previous 3 years the group reflected, deciding to hold its first group exhibition in 2005 at the Moores Building in Fremantle. Moving to a more conventional exhibition mode in a gallery was a logical step as the group had grown the dialogue around the nature of ‘Concrete’ to allow for other aspects of practice besides classic two-dimensional painting and the strictures (and possibilities) of Geometric Abstraction. To this point the wall-works had adhered to the traditional nexus between Concrete Art and Geometric Abstraction that had been cemented in the postulations of van Doesburg and Mondrian. Despite their differences, both artists, and most of what followed under the banner of Concrete Art, stuck to a rigid schema by which the play between linear geometry and colour set the agenda for making art. However, an expanded history of Concrete Art would include the work of the mid-century Brazilian neo-Concrete artists – Lygia Clark, Helio Oiticica, Lygia Pape and others – who extended the notion of ‘real experience in art’ (concretism) to include the viewer’s active participation. Similarly, by 2006, the AC4CA saw an opportunity to show work by its members that expanded the notion of what ‘concrete’ might encompass. This exhibition, the first of six so far, allowed for installations and work that did not run the ‘party line’ of Geometric Abstraction. In critiquing the first exhibition of the AC4CA as a group, Dr Ric Spencer wrote: “What has put the group on the national map, is its soft formalist approach to wall painting and there is plenty of this blend of minimalism and structuralism to enjoy with the eye. The work is a mix of retro abstract geometrics, built installation and painting with a unique blend of Euro kitsch meets Australian cement. In a collaborative sense, the mix of European and local artists makes for an intriguing cocktail”.13 This expanded field for the use of the term concrete is very much in keeping with its ongoing historical evolution. Primarily focused on real experience as opposed to a mediated one, neo-Concrete Art has, at least since the Brazilians, continued to morph, embracing new materials, strategies and environments.

In a similar vein, in 2005 the AC4CA issued its first set of silk-screened prints. The seven limited edition prints drew on the designs for the previous wall-works.14 Once again this extended the original project to include a more conventional format for presentation allowing the ideas of the project to gain a mobility and to be able to be considered in other ways than an encounter in the street, such as the later showing at Paris Concrete in 2012.

There have been several unrealised AC4CA projects, but one such project that didn’t get off the ground in 2005 drew sharp focus on the difficulty of the decision-making processes involved in public art. Initially the group had started out making walls in collaboration with the walls’ owners ignoring the standard bureaucracy needed for ‘permission’ that of course eventually resulted in the difficulties with the car park project in Fremantle mentioned above.

When invited by leading Perth architectural firm Donaldson and Warne to prepare a design for a small performing arts stage and facility on the beautiful Perth foreshore there was trepidation in the group about lending itself to this kind of scrutiny which came with the project. The suspicion was well-founded for what followed was a bizarre set of events indicative of the inevitable tension between progressive art and its ‘public’ or audience. The City of Perth received four designs from members of the AC4CA for the open-air stage and its specially convened expert panel decided upon Alex Spremberg’s comparatively innocuous design. The councillors then rejected the design, over-ruling its own panel, with one councillor – later to become a long running Lord Mayor – stating that “None of us were overly impressed”, suggesting instead school children would be asked to come up with designs, seemingly thinking they could do a better job.15 The idea of designs by schoolchildren was quickly dumped and a suggestion came forward from the Council that the students at the nearby Central Technical College, Art Department be given the opportunity. Presumably thinking the students would produce something more acceptable but not appreciating that Alex Spremberg was in fact a painting teacher there and most likely to be in charge of any such project. Needless to say he shot off a letter to the City sparking a small controversy with the councillors wearing considerable egg-on-face.

The group returned to wall painting in early 2006 with a new large wall by Alex Spremberg (AC4CA Project 9) in Henry Street located in close proximity to 3 remaining large walls in the Fremantle CBD. The starting point for the design was a gap in the middle of the top of the wall. Alex said, “Looking up the wall, the deep and brilliant colour of the sky was visible through this gap. I wanted to bring the sky down the wall to the ground, which I achieved by using the gap as the beginning of a wedge that ran all the way down the wall to the ground. Fanning out from the ground up I continued the diagonals back up the wall in analogous colours, repeating and alternating the shades. These were colours that were not seen in this vicinity and made the wall a dynamic focal point in the streetscape”.16

There were now five large AC4CA works (including the multi-storied car park) within a short distance of each other, constituting a significant visual intervention in the public space of Fremantle. This evoked further dialogue in the local press and for a short while there was additional very real community dialogue as to the value of public art and what it might be and mean. This was the most intense response to the AC4CA’s activities so far but unfortunately it resulted in stricter regulations in how the walls might be produced, requiring agreement and oversight by the City of Fremantle. Consequently the group decided to make works in other municipalities where the lack of such legislation would allow the group’s unimpeded practice while continuing to use the existing Fremantle walls for further works when possible.

It wasn’t until 2008 that the next wall-work appeared. This time by a new member of the group, Julianne Clifford, whose fascination with the aesthetics of the ‘bitmap’ (the standard representation of coded data) had seen her studio work acquire an almost diagrammatical form. She said, “The aesthetic and logic of the bitmap is proposed as a concrete universal structure conflating with the historic predecessors of plane geometry and the modernist grid. It represents an ubiquitous code and pattern embedded in our culture which is simultaneously both universal and unique”.17 The work (AC4CA Project 10), painted over Helen Smith’s previous wall painting in Pearse Street, North Fremantle, and brought a new level of complexity to the idea of ‘concrete’ to the group. Its imbedded signification and political connotation was a new turn, away from the usually disinterestedness of the previous designs. This work, while in no way ‘meaningful’ did draw attention to the possibility of pure abstraction being used for all sorts of intentions. A kind of meta-text, the work is an image of a process of representation that can be used in a myriad of ways – including the coding of information. Unlike previous AC4CA works this piece has an ethical interest, linking aesthetics in its most reduced form with behavioural and moral responsibility.

Daniel Göttin’s Project 11(2008) was the first AC4CA wall to be made outside of Fremantle by virtue of it not requiring any permission from the local authority, allowing it to be easily conceived and executed. It continued Daniel’s site-specific practice whereby the form of the building/wall generates the design of the work. Using the geometry and measurements of the facade of a gallery and residence in Gladstone Street, East Perth, he developed a design that takes it cue from the dimensions of the positive and negative spaces determined by the doorway and the windows of the building’s facade. Likewise, Alex Spremberg’s third wall work, (AC4CA Project 12, 2008,) also on the front of a building (Hasler Road, Osborne Park) used the existing geometry and shape of the facade to construct the design. The front wall of the building is often framed by a blue sky and again, as with his previous two projects, the colour is a response to the visual context and environment of the work.

Flyer for AC4CA exhibition at G&A Studios, Sydney, 2006

Despite the tightening of the regulations around public art in Fremantle and especially wall works, during 2009 and 2010 four new paintings were achieved on existing sites. John Nixon made a new design for his wall in Leake Street (AC4CA Project 14, 2009) – this time vertical bands of silver and white followed by a new work by Jurek Wybraniec (AC4CA Project 14, 2009) painted over Jan van der Ploeg’s design on the Cantonment Street wall. This was a dramatic departure from all previous AC4CA walls with a strong ‘organic’ feel to the work and little apparent geometry at play. Using the Airbrush tool in Photoshop Jurek allowed for the clumsiness of this early digital painting process to draw vertical lines and stripes of colour over a field of blue to generate a deliberately exaggerated garish design. A kind of crazed minimalism, this image combines the Popism of high key colour, a reduced structure (bands or stripes) with the wonkiness of primitive digital technology. A bit of an ‘eyeful’ for sure but one that was delightful and provocative in its experience and presence.

Jan van der Ploeg returned to Perth in 2010 for an exhibition at Goddard de Fiddes and to make another wall in Fremantle. He painted a new black and white design over Alex Spremberg’s piece on the Henry Street wall. AC4CA Project 15 (extant) is a stunning pattern that has a shifting visual field that flips from large to small squares, from horizontal to vertical and diagonal bands and plays with negative and positive space. It is a dynamic pattern that cannot settle, continually changing and morphing yet beguilingly simple in its black and white surface. Like all of the AC4CA’s walls – the more time you spend looking, the more visual response it will provide. This is the essence of Concrete Art – a simple design that evokes a pleasurable visual experience.

Since the 1970s when he started to extrapolate drawings from the floor and wall plans of buildings he had found on his travels through Africa, Asia and Australia, David Tremlett has made work that can be described as neo-Concrete. David’s long association with Western Australia began in the early 1970s when he first visited family that had migrated there. Indeed it was on the return trip to England overland that the work he would become so well known for started to develop. A kind of record of a place or even a visual memory, his on-the-road drawings, especially of buildings, started to be translated directly onto walls themselves through pastel rubbings that abstracted the buildings’ plans and re-contextualised them. They suggest a visual language shared by all buildings in their basic architectural design; proportion, scale, negative and positive space and so on. David’s design for his Fremantle wall (AC4CA Project 16, 2010, extant), painted over Jurek Wybraniec’s very colourful image on the Cantonment Street wall, is an extrapolation of a wall work realised in a Palladian building in northern Italy, Villa Pisani Bonetti, just before coming to Fremantle. The flat-paint colours used in the work mimic the pastel texture and colours David uses in his interior wall-works. David’s works can be found all over the world and collectively they form a kind of network of related images. This work integrates Fremantle into his larger project spread across the globe. After this work, as part of a review show at the Hamburg Kunsthalle later in 2010, he made a work that used Western Australian placenames for a large wall drawing making a tenuous connection between Australia and Germany.

Eventually the difficulties of realising walls in Fremantle because of the strictures of the City’s regulations led to an invitation from the City of Subiaco and the making of four walls over 2011 and 2012. Three of these are ‘wrap around’ designs that move over the surfaces of box-like structures. Helen Smith’s Project 17, 2012 (extant) realised a design for a wall painting first proposed for Fremantle that was rejected in the planning process. The facility-box in Alvan Street, Subiaco has a striped blue and white pattern painted around it that was originally a flat, two-dimensional image. In adapting her design to the box Helen’s painting exaggerates its shape as the colour and the wave-like rhythm of the pattern turn the box into an art object. A peculiar and unexpected cube dropped into an otherwise drab and dreary environment. Similarly Daniel Göttin’s Subiaco work (AC4CA Project 18, 2011, extant) articulates a three-dimensional space across two articulated walls. The step and fold construction of these walls gives the green, black and white design a depth that makes walking past the work a complex experience as various surfaces move next to each other in the visual field. As with all his work, the geometry and shapes of the walls generate the pattern, so on this multifaceted wall-face there is an even more dynamic relationship between the blocks of colour as the changing shapes they produce as you move past the walls consistently reconstruct the pattern and the shape of the image.

Jeremy Kirwan-Ward joined the group in 2010 after assisting on several walls beforehand. A very well known painter in Perth over many years, he began using colour field abstraction at art school in the late 1960s and his obvious simpatico with the intentions of the AC4CA made him a natural fit. His beautiful work (AC4CA Project 20, 2012, extant) on another box-like structure in the middle of Subiaco’s main shopping precinct is successful because of its three-dimensional experience, enjoyed as pedestrians and cars move past it, catching the joins in the pattern that is replicated on all four sides of the structure. This tessellation gives the box not only an uniformity, but also a visual depth that is heightened by the design which uses a strict interpretation of the proportion of the box.

Unlike the previous gallery exhibitions, the 2012 AC4CA installation at FABRIKculture in Hégenheim, France (Project 21) was an opportunity for the group to make large interior wall paintings similar in scale to the outdoor public walls in greater Perth. The exhibition, which was organised by Swiss artist and curator Gerda Maise (which also included the complete set of silk-screened prints), allowed for a better sense of the group’s connected practice by placing all the artists together in the same very large space.18 The dialogues between the works and the consistency of the aesthetic made for a convincing realisation of the group’s shared artistic sensibility: a kind of Minimalist hybrid that requires no explanation or justification in its colourful reductionism and pared-down design. The Hégenheim show made for a collective statement around this sort of art making but at the same time it did so without any insistence or demand for affirmation or response. Concrete Art has always been, at its heart, non-judgemental, requiring no pre-conceived ways of seeing or understanding other than participation and experience. This kind of ‘disinterestedness’ is what Kant saw as the distinguishing quality of aesthetic experience – an act unfettered by meaning and reasoning.

The most recent exterior wall work to be finished in the City of Subiaco was Darryn Ansted’s, on the sidewall of a showroom in Rokeby Round (AC4CA Project 19, 2011, extant). This elongated work is a complex interpretation of the dimensions of the wall overlaid with an anamorphic grid so that the pattern appears to be a square at a particular point of viewing near the street end of the work while distorting as you move past the wall and then returning to a square at the end of the wall. Like Jeremy’s Project 20 the colours reflect the surrounding palette of the foliage – greens and lavender, contextualising the painting and softening the geometric lines and shapes. Similarly Darryn’s, and the AC4CA’s, most recent outdoor work (AC4CA Project 22, 2014, extant) uses the same strategy to deal with a similar shaped wall in South Fremantle. Painted in a laneway on the side of a terrace house, the work uses the same strategy as the Subiaco piece, but this time uses two tones of blue specifically to contextualise the wall in terms of its proximity to the sea that can be glimpsed from the adjacent road. This wall, while domestic in scale, continues the original intention of the AC4CA - to make public interventions that enliven the everyday public domain.

The sixth AC4CA ‘gallery exhibition’ (One Place After Another: AC4CA Project 23) in collaboration with the Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts (PICA) allowed for the expanded group, which by November 2014 included French artist Guillaume Boulley and Berlin-based Zora Kreuzer, to use the gallery’s large walls to present a series of wall works that collectively construct a visual dialogue between the differing aesthetics of the group’s artists. As an installation it is an emphatic statement about the consistency of thought and purpose of the 13 AC4CA members, demonstrating their similarities and continuing references to the historical aspirations and intentions of Concrete Art.

In her essay describing the artworks in One Place After Another, Curator Leigh Robb picks up on the cross-generational and international composition of the AC4CA membership that has been a distinguishing aspect of the group’s dynamic since its inception. This attests to the currency of the group’s interest and the nature of Concrete Art, that in many ways sits outside the conventions of contemporary art. Concrete Art was never a part of the grand narrative of modernism – ironically though, its perceived style (if there is one) could easily be substituted for many of the visual hypotheses of modernist painting – reduction, simplicity, formalism, etc. However this art, while stridently democratic, has a tradition of being uncomfortable within popular histories of the art of the 20th and early 21st century that chronicle a continuing story of changing dominant styles or types of avante-garde practice. In a contentious way the practice of Concrete Art transcends these histories, having maintained relevance and currency for nearly a century. As a continuing practice Concrete Art could now be said to be trans-historical. This is probably why it does not look or behave like most contemporary art – but it is also neither sentimental nor anachronistic. It continues to be un-contemporary.

Over the past 12 years the Australian Centre for Concrete Art has matured as a project, growing and extending its activities internationally. The success of the AC4CA in continuing to develop the way it has is as much due to the slowness of the project as to anything like ambition or good planning. It has managed to evolve in a way that reflects its opportunities and possibilities while staying true to the initial intention of supporting and presenting neo-Concrete Art in the public domain and thus making a delightful contribution to the everyday. This clear intention continues to direct and drive the group.

In 2006 curator and writer Gary Dufour, then Deputy Director of the Art Gallery of Western Australia, said of the AC4CA:

“This is what I appreciate about AC4CA, the ambition of each of the artists to put a new visual proposition out into the world, using a palette of colour to structure our perception and experience of space. Their individual and collective efforts continually provide new tools for deriving visual pleasure from everyday experiences, allowing us to recognize the little visual epiphanies the attentive encounter throughout the world, which arrest, if only for an instant, the habits of perception and transform them into rich visual discoveries”.19

In many ways this has been the essential remit of the AC4CA – to bring pleasure and beauty into the world.

__

1./ Beginning in Fremantle and moving to the Perth CBD in 1996, Goddard de Fiddes Gallery ran from 1992 to 2012. Initially the gallery aspired to support the practices of artists that sat somewhere between a neo-Minimalist and a post-Pop sensibility. The gallery concentrated on showing what was dubbed ‘West Coast Geometric Abstraction’ – a reference not only to the group of artists affiliated with the gallery but also several shows of historical art of this tendency in Perth and Fremantle going back to the 1950s.

2/ This project was in line with the establishment of several early (and future) organisations I had established before Goddard de Fiddes Gallery with Glenda de Fiddes in 1992. These included the WA Artworkers Union in 1979; Parameters in 1980 with Brian Blanchflower, Bruce Adams and John Robinson; the re-establishing of Praxis in Fremantle in 1981 with Theo Koning and Mark Grey-Smith (Praxis evolved into PICA), the journal Praxis M and The Beach (gallery and studios) in 1987.

3/ Australian Centre for Concrete Art constitution.

4/ See Acknowledgements for a full list of the various members.

5/ One of these businesses was owned by the then Mayor of Fremantle who became engaged with not only Trevor’s stunning piece but with the larger AC4CA project. He later supported the very contentious Project 7 – the painting inside and out of the Queensgate car park in Fremantle.

6/ From an email to the author, 23 October, 2014.

7/ The Fremantle Society was established in 1972

to champion the heritage built environment

of Fremantle.

8/ John Dowson. President, The Fremantle Society quoted in The Fremantle Gazette, Community Comment, 11 March, 2003.

9/ The West Australian, 20 June 2005, p.3.

10/ The Sunday Times, 7 July, 2006, unpaginated.

11/ The work was made on a wall of a small car park in Pakenham Street, Fremantle. While still there it can no longer be seen because of a new building on the car park which butts up almost to the wall only leaving a small gap where the painting is still just visible.

12/ All traveling to Perth for exhibitions at Goddard de Fiddes.

13/ Dr Ric Spencer, ‘Hard but Fair’, The West Australian: Weekendextra, 26 November, 2005, p.13.

14/ There had been eight walls by 2005 but two were by Jurek Wybraniec. He chose to make only one print: the ‘water tank’ project.

15/ Cr. Lisa Scaffidi, The West Australian: Inside Cover, 18 February, 2005, p.2.

16/ In an email to the author, 23 October, 2014.

17/ Ibid.

18/ FabrikCuluture is a large not-for-profit art space in Hegenheim (Basel), France in a converted textiles factory that host ongoing exhibitions of international contemporary art.

19/ Gary Dufour, Foreword to the catalogue for AC4CA 2005 The Moores Building Contemporary Art Gallery, Fremantle, Western Australia, 18 - 27 November 2005.